Tulipmania & Taming Irrationality

#

My quest to understand market speculation —rather than relying on lazy quips about “animal spirits” or irrationality.

“Tulpenwoede” An Intro

Once in the Netherlands, tulips were worth more than real estate. Legend has it that in the 1630s, a sailor was thrown in a Dutch jail for eating a tulip, thinking it was an onion. At the time, the sailor’s gluttony would have fed an entire crew.

Does an asset price rising to crazy heights with the help of ordinary investors hoping to avoid missing out sound familiar? It represents one of the earliest instances where asset prices deviate from intrinsic values.

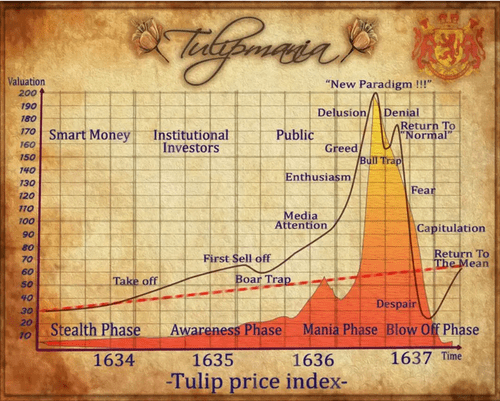

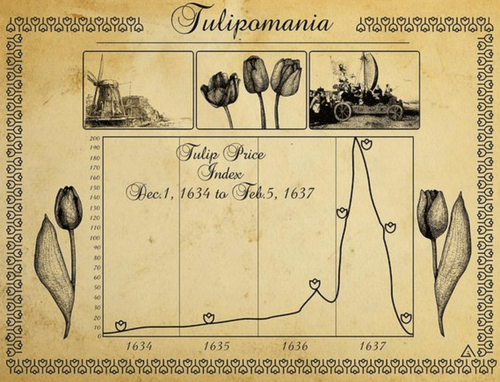

During the period, wild speculation and euphoria of the masses led to “irrationally exuberant” spending on these bulbs. Ordinary citizens, even to the lowest dregs, were trading tulips. Properties were converted, assets to cash, and invested in flowers. Houses and land were sold at ruinously low payments at tulip markets. These tulips were loved for their deep, bright colors and exotic appeal and didn’t experience price swings due to changes in production costs. Nor did they find new utility. Their popularity coincided with the Dutch Golden Age, where the republic was one of the world’s leading economic powerhouses.

Per David Roos, post the 1620s depression, “…the Dutch enjoyed a period of unmatched wealth and prosperity. Newly independent from Spain, Dutch merchants grew rich on trade through the Dutch East India Company. With money to spend, art and exotica became fashionable collector items. That’s how the Dutch became fascinated with rare “broken” tulips, bulbs that produced striped and speckled flowers.”

During the event, historian Mike Dash mentions. Dutch artisans worked long hours for low wages. “When the day’s work was done and they could finally go home, it was to cramped and sparsely furnished one or two-room houses that were in such short supply the rents were high…to people trapped in an existence such as this, the idea that one could earn a good living by planting bumps and sitting back to watch them grow must have been irresistible.”

Post the rampage of The Bubonic Plague, there was a labor shortage, leading to higher wages and extra income for those who worked. Plus, the plague meant widespread lowered risk-aversion. The Dutch were fine indulging in speculation, knowing that each day could be their last. There was a post-plague “mood of fatalism and desperation,” aiding speculation and reckless spending. The rich are accelerating prices even higher, buying rare breeds of tulips. Combining these factors, tulips increased in popularity as a means for people with disposable income to acquire wealth for the first time in many years.

Tulips were being sold for more than 10x the annual income of skilled artisans, and people kept on pouring life savings into buying tulip contracts anyway. When confidence was at its peak, everyone imagined their passion for tulips would last. I’d imagine those profiting trading bulbs could not resist telling family and friends of their good fortune.

There are stories of a man that sold his house in Hoorne Town for three bulbs — i.e. the first speculative bubble in history.

Calming Hand Taming Irrationality

Like all bubbles, in 1737, the market burst with groups of auctioneers lowering prices with no buyers. Due to the lack of interest, the market disappeared entirely in the coming days. However, investors acted rationally. According to Nicolaas Posthumus, a Dutch historian, serious tulip financiers generally did not participate in the speculative markets. The “mania” was usually self-contained within smaller circles and pushed by “casual traders”.

It is easy to claim that bubbles are irrational. They seem to represent a deviation of prices from fundamental values and contradict the basic economic theory. But there has been little attempt to understand the details of how speculation and the government are intertwined.

Earl Thompson argues the market for tulips was an efficient response to the government conversion of futures contracts into options contracts. This was a deception by the government officials hoping to make a quick profit. The conversion meant investors who had bought the right to buy tulips in the future were no longer obliged to buy them. If the market price isn’t up to one liking, the investors had the option to pay a fine and get out. This increased tulip options prices, then collapsed when the government saw sense and canceled these contracts. The spot price and futures prices weren’t volatile. Tulipmania was only a contractual artifact. Contrary to popular interpretations, there was no actual “mania.”

The critical concept of preventing actual “mania” from happening is thus the government’s calming hand. During the dutch times, corrupt officials realized their pursued ruse would cause mania, and stopping the conversion was a calming hand to their own doing. Nowadays, the government buoys speculators through unconventional monetary policies like quantitative easing — printing money to buy government bonds and mortgage securities.

The calming hand of governments nowadays is through unconventional monetary policies that are deemed to not encourage speculation — rather dampen it. However, economists worry that investors have come to rely on this calming hand of central banks. Unconventional monetary policy has been attacked for promoting further financial gaming. When it is taken away, speculative urges return. Central bankers might feel pleased with themselves for having tamed “animal spirits,” but market uncertainty edges back in the weeks after monetary policy intervention.

This reliance has developed to a point where now, without regular interventions, markets become increasingly skittish. Central banks used quantitative easing and other monetary policies to save the world from financial meltdown. But easy money repressed, rather than extinguished, speculative practices. To feel comfortable halting these unconventional policies, central banks must ensure that the probabilities of nasty-tail risks have fallen. But can they ever do that? Hmmm…?